Michael J. Masucci is an award-winning experimental media producer, artist, writer, curator, educator and musician. He is notably a founding member of the trailblazing and historic video art group and alternative theatre/gallery space, EZTV, and along with computer art historian Patric Prince, also created CyberSpace Gallery, one of the world’s first art galleries dedicated to digital art.

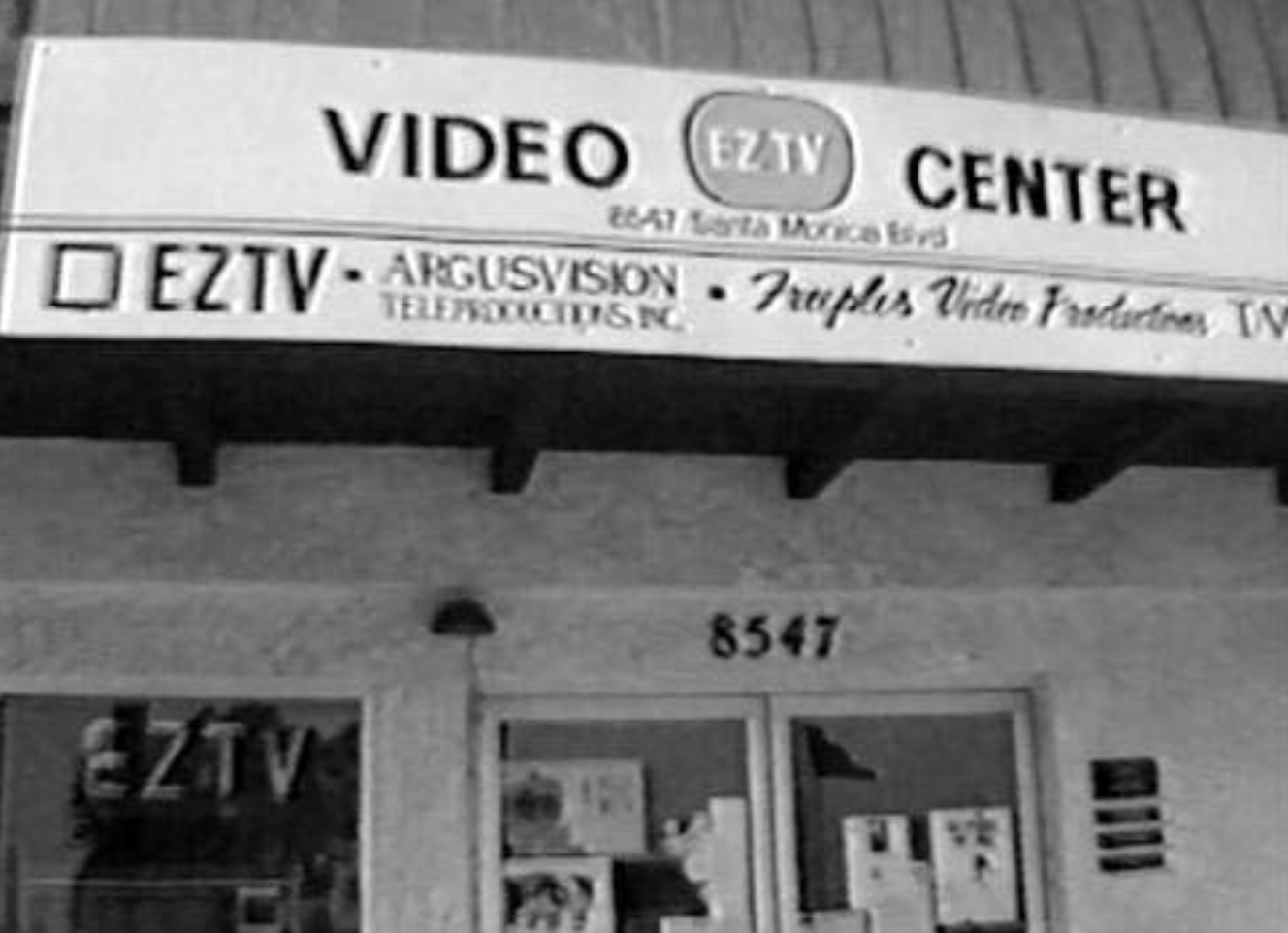

EZTV’s roots began in 1979 when founder John Dorr, after years of attempting to work in the Hollywood film studio system, began experimenting with home video equipment. Dorr and several other video makers began creating feature-length films and holding evening screenings of their work at West Hollywood’s Community Center. This began the local concept of a legitimate theatrical-style 'video theatre', better known today as microcinema. In 1983, John Dorr and a group of over two dozen co-founding members pooled their resources and skills to create a permanent space for the screenings. These members include Michael J. Masucci, James Williams, Mark Shepard, Patricia Miller, Sondra Lowell, Robert Hernandez, Nicholas Frangakis, T. Jankowski, Pat Evans, Earl Miller, Jaime Walters, James Dillinger, Phoebe Wray, and B.A. Falvo. The small space was called “EZTV Video Gallery”.

As the American Film Institute noted, EZTV Video Gallery was “the first independent gallery to dedicate all of its space, all of the time, to ‘the box,’” while V&A curator Melanie Lenz credits it with "literally putting digital art on the map.”

Rodni: You’ve described EZTV as a "bombarding" of two aesthetics – John Dorr’s love for traditional narrative cinema and his “DIY” philosophy, versus your own interest in state-of-the-art production and experimental digital imagery. How did this tension create the unique DNA of EZTV? And how did it affect your curation of events?

Yes, there were two simultaneous directions: a large group of people looking to make feature-length narrative work on video, and a smaller group, including myself, looking to create more experimental, and often non-narrative projects. Both groups curated work that supported their own tastes.

The programs evolved accordingly. What had begun as predominantly video-based soon expanded to include gallery wall exhibitions and live performance. As the years passed, several different persons, each presenting a distinct curatorial voice, emerged. I was one of them. The result was a space that transformed nightly. This was more similar to LA’s nightclub scene at the time, when different themes: Queer, Goth, Punk, etc., would be featured.

With multiple curatorial perspectives sharing a single venue, a larger conversation, if not tension, took shape. We thought about what alternative art spaces in Los Angeles could be. And who they could serve. This was the early 1980s, and the AIDS Pandemic was already devastating the local community. In response, EZTV quickly became not just a site of exhibition, but a gathering place for activism, for mourning, for organising, for healing. And for thinking independently.

Collaborations occurred that might never have been possible had we been ‘siloed’ into a specific genre or even technology. My own work as an artist informed my work as a curator. And vice versa. And the other artists and curators informed me as well.

Within the first year, EZTV was already more than a video gallery. We were functioning as a gathering place for the community as well as the more fearless members of both Hollywood and the art world. The public noticed. So did the press. Audiences ranged from curious neighbours and friends to artists, filmmakers, musicians, and a few prominent cultural figures. Everyone seemed to move smoothly between the underground and mainstream worlds. EZTV wasn’t just a venue anymore. It was a scene. In some regards, there were similarities to some of the DAOs of recent years.

Rodni: You’ve noted that "in one sense we were all outcasts at EZTV," including LGBTQ+ creators, "geeks" from the SIGGRAPH crowd, and punk artists etc. At what point did this collection of "outliers" start to feel like a cohesive movement? Was there a specific event, moment in the media, or a specific time where you began to recognise the influence of EZTV on the art world? Or did this only come with hindsight?

I think by 1986–87, we knew we were a type of movement. People began reaching out to us from the mainstream. I was invited to sit on the board of a new county-wide arts festival and was asked to judge for awards and grants offered by the American Film Institute and other institutional organisations. Then something unexpected happened that quickly drove us forward. We had an overnight success. And it wasn’t even something that any of the core EZTV members created. It was something we presented. John Dorr curated a feature-length documentary about writer Jack Kerouac, directed by Richard Lerner & Lewis MacAdams. It became a genuine runaway hit. It ran for months, and we needed to rent three additional screening rooms across town to accommodate all the people who wanted to buy a ticket. At the time, the press called it the first ‘video theatre hit’, and among the first instances in which a feature-length work, shot and exhibited on video,was openly competing with mainstream cinema. Plus, rather than a fictional work, with movie stars or special effects, it was a documentary about a poet. No one expected this. Frankly, not even us. Audiences grew more comfortable with the idea of leaving their home and paying to see independent video. And stopped seeing its “look” as a technical compromise. In fact, some people began to prefer video. A kind of ‘hip factor’ developed. EZTV became ‘cool.’

This success enabled EZTV to expand from a small, modest gallery into a sprawling, multi-floor facility, increasing both our ambitions and our reach. A professional computer graphics workstation was donated, greatly expanding our technical capability. Around the same time, in 1986, I met Kim McKillip, also known as ia Kamandalu, and what would become Vertical Blanking began to take shape. The spirit of experimentation was everywhere. Our growing involvement with groups like LA ACM SIGGRAPH further solidified our ties to emerging digital and computational art communities.

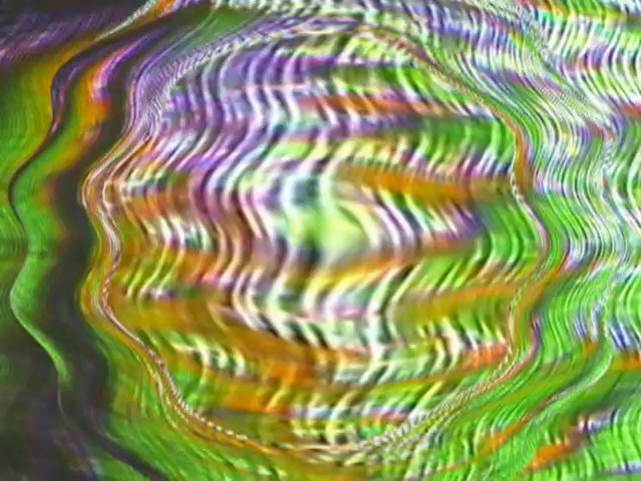

The emergence of work, usually short form, being made on computers and then transferred to video, greatly broadened the spectrum of work we were showing, and really differentiated us from traditional movie theatres. Works by computer artists/animators such as Rebecca Allen and Shelly Lake strengthened the commitment we had shown since our earliest days to being a place where digital art could be seen.

I would categorise EZTV’s early history as “pre-1986” and “post-1986.” By 1987, the early tension largely fell away, and a direction emerged. Over the following years, EZTV steadily evolved into a more intentional home for digital art and performance, yet still hybrid, and continuing to embrace all forms of electronic media, as well as live and traditionally based work. We were artists who supported other artists, who together supported each other, and largely operated outside the system of grants or institutional support. By 1988, the feature-length narrative side of EZTV, with a very few exceptions, was largely over. Documentaries, digital, and performance art were taking over.

Not everyone welcomed that evolution. Some felt that we refused to align ourselves with the dominant trends of either Hollywood or the contemporary art world. In a sense, they were right. We had no interest in doing what everyone else was doing. I suppose that was the point. Because we were volunteering our time to curate and present other people’s work, and made our living through our work as professional video-makers and artists, we saw no reason to present what was already out there, in either the mainstream of Hollywood or the more elitist world of contemporary art. And as is often the case, that refusal to conform made us both visible and vulnerable. Some people disliked it then. Some still do. But enough liked, even loved it, and supported us for now 47 years.

"Polly Gone" by Shelley Lake

ART 1990 was a seminal show that impacted the trajectory of EZTV and ultimately led to the creation of CyberSpace Gallery.

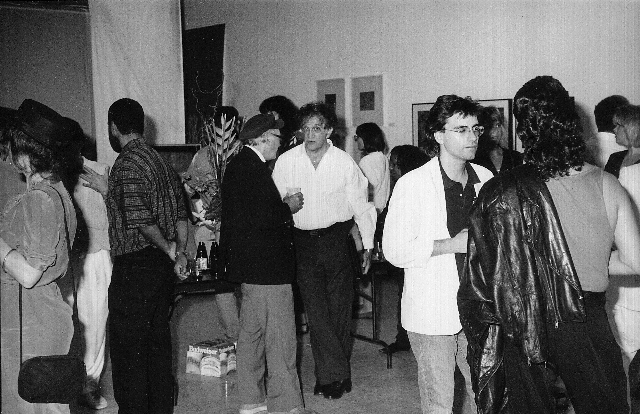

Rodni: Could you take us back to those early EZTV events? What was the overall atmosphere or vibe like in the room during the set up, and then during a typical screening or performance night? Was there a particular energy that defined it? And what set these gatherings apart from the standard gallery exhibitions of the time? Why do you think that unique approach resonated so strongly with people and drew such a diverse crowd?

At first, it was very intimate and very casual. Very different from a formal movie theatre or a stuffy art gallery. A tiny room with two TV sets playing the videos. Crowded, almost claustrophobic. The seats were cheap and uncomfortable, but no one seemed to care.

People have told me that there was a palpable energy one could feel just prior to the start of a screening. What would be seen? Would it be heartfelt, funny, informative, or shocking? Or in a few cases, all of the above? Who would they run into? Would any movie or rock stars, or politicians, trying to be hip, be sitting inconspicuously at the back of the room?

And sometimes there would be an almost circus-like aspect. This was most noticeable during the monthly art openings, when a mix of wall art, some experimental video or digital art, and often outrageous live performances would all share the evening. Of course, these openings were free and open to all, with cheap wine given away freely. But conversely, when more traditional narrative-style feature-length work was being screened, the vibe was more like attending a movie screening. The director would introduce the piece, take questions, and hope for some widespread recognition. And as the AIDS Pandemic ravaged the 1980s and early 1990s, there was the somber side. We’d donate the space to several AIDS awareness organisations for public meetings, and offer the space, free of charge, to anyone, so they could hold a memorial service for a loved one who had passed away because of AIDS.

Most galleries treated video almost as sculptural, monitors perched on pedestals, looping endlessly, encountered mid-stream as viewers wandered past. The experience was fragmented; you caught a moment, then moved on, never quite settling into the work. Often, never even seeing the entire piece. The imagery was often disparagingly referred to by some as “wallpaper.”

What we were proposing ran counter to that logic. EZTV asked audiences to stop, sit, and watch. To give video the respect traditionally reserved for film.

Live digital multimedia/music pioneers InTone combining live and sampled music/sound design synchronised to a variety of imagery on computers, video monitors and projectors. Such live technologically sophisticated performances were still extremely rare at the time, and EZTV was among the only art spaces in Los Angeles that routinely advocated for digital art and performance.

Rodni: You described EZTV as a “socio-political petri dish", where an open door policy and humanist approach meant that people from every background were welcome, even if they did not fit the societal or art world norm at the time. “Separatism was never the goal. Independent video was.” Can you dive more into why this was so important to your mission at EZTV? And can you talk about the challenges you faced being marginalised and misunderstood by people in the art world and how you overcame them?

To really understand EZTV, it’s important to understand where it came from, and just as importantly, what it refused to be. I am a straight, cisgender man. But many of EZTV’s founding members, including its founder John Dorr, were openly gay men at a moment when such self-identification carried real professional risk. As a result, queer culture and the urgent politics of human rights were undeniably present from the outset. Yet what distinguished EZTV was not simply who was represented, but how representation was framed.

At the time, Los Angeles already had alternative art spaces explicitly dedicated to historically marginalised communities. Among the most renowned was the Woman’s Building, an institution of enormous influence and artistic merit. It helped define what alternative art spaces could be. We all had deep admiration and respect for that space. John Dorr could easily have positioned EZTV in similar terms, he could have named EZTV, quite literally, “the Gay Building.” He chose not to. Instead, he made a radical decision: video, not identity, would be the focus. Yet, everyone recognised the queer roots of the space. I have often thought EZTV could never have happened in a straight cisgender space. The largely gay community, who were the earliest members, wanted inclusion. Queer culture was highly visible, unmistakable, and deeply embedded in the early narrative works produced at EZTV; it was obvious and taken as a given. But as I said, it was video, the medium of choice presented, that was the point.

Cultural pluralism wasn’t a slogan, a talking point, or a funding strategy. It was simply our reality, and frankly, I can’t recall anyone ever even talking about it. We believed we were obligated to present strong work even if it wasn’t to our personal taste. Or lifestyle. Or identity. If a piece was either rigorous or outrageous and authentic to the artist’s vision, we would stand behind it. This position unsettled many within museum and academic culture, who criticised us for lacking focus, credentials, or the conventional markers of expertise. And yet, critics kept responding positively to the work itself, and they kept writing about it.

And history has a way of circling back. In 2025, curators Elizabeth Purcell and Alex Gooter mounted retrospective screenings of EZTV in both Los Angeles and New York, focusing on many of the earliest works, an acknowledgment that what was once caricatured or ignored had, in fact, helped shape a lasting alternative model.

Rodni: It seems almost surreal that your professional equipment was provided for five years at no cost by Avi & Leah Bahr, a politically conservative military man and his wife who joked they were "to the right of Attila the Hun". Can you explain this relationship?

Yes, some of our most professional equipment in the earliest days was loaned to us by a couple whose politics, religiosity, and world views could not have been more different than our own. This, ultimately, was so inspiring, a lived, uncompromising respect for diversity. Not only the familiar categories of gender, sexual identity, ethnicity, national origin, physical ability or age, but something far more fragile and far more endangered, the diversity of ideology. That principle, once foundational to American cultural life, especially in academia as well as the artworld, now feels perilously close to extinction.

Avi and Leah didn’t advertise their values; they simply lived them. Their commitment wasn’t rhetorical or conditional. In fact, few people involved with EZTV even knew about them. There was no public acknowledgement of their gift. No plaque on the wall. Most artists never asked where the equipment came from; they simply used it. This taught me in such uncertain terms the meaning of true integrity. Avi once told me that he and his family were often horrified by the work being produced with the equipment they were generously lending us. They found some of it abrasive, misguided, even offensive. And yet, he said, without hesitation, that he would give his life to defend our right to create that work, and to show it publicly.

That distinction matters. Approval was never a requirement. Creative freedom was. Avi believed, deeply and without self-aggrandisement, in what many of us were taught. And that was to regard as one of America’s most essential promises, the right to express ourselves. Especially when that expression unsettles, contradicts, or challenges prevailing beliefs. In that conviction, lived rather than proclaimed, was a model of integrity that feels increasingly rare and increasingly necessary.

Rodni: By the late 1980s, the press was paying such serious attention to EZTV that core artists achieved "near rock-star status". Can you explain what this time was like for EZTV and how the curation and events might have evolved with this surge in public recognition? And how did you stay true to the mission of supporting diverse, underrepresented, and experimental artists when there may have been pressure or influence to shift toward more predictable programming that would appeal to larger, mainstream audiences?

Looking back now, it’s still slightly embarrassing to recognise that we were, in our own way, well-known. And that EZTV had an audience, even fans. I had an early performance art persona called “the Videoholic”, and every so often, I’d be walking down the street when someone would shout from a passing car, “Hey, it’s the Videoholic!” Once that started happening, I stopped making any more Videoholic videos.

We never allowed recognition to shape what EZTV did next. Nor ever pivoted toward what we imagined people wanted from us, or what might increase popularity. If anything, we resisted it. Beneath the occasional “bad boy” posture was a serious conviction that we were part of a community and that we owed something to that community. To both create as well as curate work that stood as deliberate alternatives to what dominated television screens and movie theatres. And I think in many ways we succeeded in that mission.

Olena: You’ve been active in the art space since the 1980s. How do you find the consistency and inspiration to continue working in the art industry through all of its ups and downs?

I’d be lying to say that it’s ever been easy to create or present work that is not immediately commercially accessible. To not follow trends but hopefully anticipate the next ones. It’s gratifying knowing that we are exploring what may likely be widely explored by others in a few years. There has always been an aspect of EZTV that has correctly anticipated where the media, the technology, as well as aesthetics, would be going next. In 1979, EZTV recognised the immense power of independent low-cost video. We were already online in 1984, we did our first international interactive online event in 1987, we were working within telepresence by 1990, and created not only among the first microcinemas but then also among the first galleries dedicated to digital art. We then had one of the earliest websites displaying digital art, and by 1999 were seeing, when few others were, that mobile communications were going to change everything. In 2003, I was quoted in the catalog for the 30th anniversary of SIGGRAPH saying “Mobile communications may well be the electric guitar of the early 21st century, and the emerging mobile digital culture may be its rock 'n' roll.” Today, we take that for granted, but many in the art world back then were resistant to the inevitable change to ubiquitous digital devices that was before them. Many still are resistant.

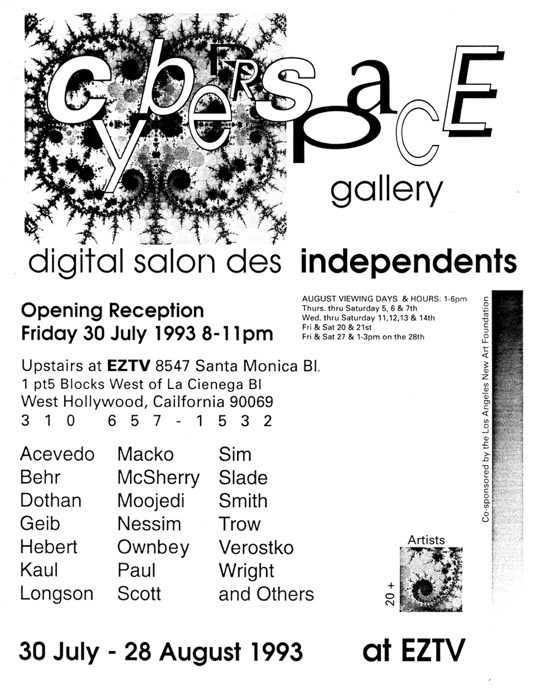

Rodni: CyberSpace Gallery was founded in 1992 as an evolution of EZTV's long-standing interest in computer art. What sparked the decision to create a dedicated gallery space at that particular moment?

CyberSpace Gallery was, as you say, a logical step to formalise a commitment to digital art dating back at EZTV to the early 1980s. Digital artist Victor Acevedo introduced me to art historian and curator Patric Prince in 1989, when they proposed a major group show on digital art at EZTV. Patric was among the first art historians to see the immense implications of digital art. Her archives are now a central part of the Victoria & Albert Museum’s computer art collection. Patric curated for EZTV a pivotal group show of computer art in 1990. The show, called “Art 1990,” was very successful and a turning point for both EZTV as well as co-sponsor LA ACM SIGGRAPH and the LA computer art scene as a whole. The following year, Patric suggested that she and I create a gallery dedicated to computer art. This was still extremely rare and definitely much needed. The following year, CyberSpace Gallery opened and received press attention in both the mainstream press and the tech press.

Rodni: You co-founded CyberSpace Gallery with Patric Prince, alongside contributions from artists like Victor Acevedo, ia Kamandalu, Michael Wright, and others. Can you describe the key collaborations and roles in getting the gallery off the ground?

There were several key collaborations and collaborators. Patric curated three shows at CyberSpace, and I curated several others, as well as some panel discussions. Artists such as Victor Acevedo & Michael Wright, our intern Lisa Tripp, and an enthusiastic group of volunteers, mainly from LA ACM SIGGRAPH, help build and paint the walls, install lighting, and help open the space. Their support was essential in immediately creating the community around the space. The space was funky and looked home-made. Which it was. Victor also helped in many other ways, logistically, and helped publicise and promote. He designed the announcements for many of the events.

Dr. Timothy Leary curated and performed at a series of live multimedia performance/lecture events. UCLA scholar Peter Lunenfeld produced an exhibition and panel discussion. Multi-screen artist Jon 9 presented a massive 9-monitor video wall installation.

ia Kamandalu and I were among the core staff members of EZTV. Our daily labours, making videos, creating demos for people, and editing their videos, paid the rent that kept EZTV and therefore CyberSpace Gallery alive. This formed the financial support for the space. John Dorr had come up with the idea of closing EZTV’s production studio and giving it to CyberSpace as its location. But John was already very ill with AIDS, and the physical space only lasted two years. We soon went virtual, becoming one of the first online galleries, certainly among the first to showcase digital art.

Rodni: In your book, ‘History is the Art of Forgetting’ you discuss how when art history fails to adopt a procedure similar to cultural anthropology, it results in culture being "degaussed" or erased. This "fashion-based subjectivism" asserts the superiority of certain designs or movements based on the underlying motives of those in power. Consequently, the official history of contemporary art is often merely an accounting of collector-based art, forgetting the cultural eco-system of alternative spaces and movements that actually fostered innovation. Do you think a more technologically advanced art world, where digital verification and transparency via the blockchain is a remedy to this?

Absolutely. What we’re witnessing now is the emergence of cultural ecosystems that are actively expanding power away from the small, elite art establishment and distributing it across a far more decentralised and pluralistic terrain. The contrast with even a decade ago is profound. One widely cited study revealed that between 2007 and 2013, roughly one-third of all major solo exhibitions in U.S. museums featured artists represented by just five galleries. I repeat, five. The concentration was astonishing, and, frankly, unacceptable. Something had to change.

And to a measurable extent, it has. The field today is undeniably more diverse and inclusive than it was then. Of course, those same five galleries continue to exert enormous influence over the mainstream art economy. Perhaps they always will, at least within that particular sector of the cultural landscape. And I see nothing wrong with that. These galleries have tremendous expertise and have done good work. But what has changed is the existence of alternative pathways. More entry points. More routes around the gatekeepers. Blockchain technologies, for all their volatility, have dramatically widened the field of possibilities. And remember, we are still at a very early stage of its development.

But still, reality matters. Structural change never arrives overnight. Market cycles, crypto winters, and NFT winters are not signs of failure so much as symptoms of maturation. Every major shift in digital distribution has followed a similar arc, an explosion of access, mass onboarding, and consumption, followed by consolidation, correction, and recalibration. And each new tech application makes people dream of immediate success. YouTube made it possible for anyone to distribute video globally. A tiny fraction of creators became millionaires, but most do not. Social media produced a handful of influencers, but the vast majority remain unnoticed. NFTs are no different. And we can’t expect them to be. A small number of artists will emerge as stars. Most won’t. But the crucial shift is that far more people now have a genuine chance to be seen, valued, and supported than ever before.

In truth, this isn’t a departure from art history; it’s a continuation of it. Countless people have painted in oil, but only a few have sold their work, and fewer still have sustained full-time careers. Art has always been difficult to monetise. What contemporary digital distribution offers is not a guaranteed promise of success, but a recalibration of the odds. That in itself is a significant improvement. The playing field is still uneven, but it is undeniably more open. And in that opening lies the possibility of a cultural future that is less centralised, less exclusionary, and far more alive. And as markets mature and stabilise, a new ecosystem between artists, collectors, historians, museologists and the art-loving public emerges.

Rodni: From curating experiential art shows, to predicting the rise of video editing on personal computers and founding CyberSpace Gallery, one of the world’s first galleries dedicated to digital art, you’ve proven yourself to be ahead of the curve over and over again. What were your initial thoughts when you learned about blockchain technology?

As far as blockchain is concerned, I was actually not ahead of the curve. A colleague introduced me to blockchain in 2020 through LA’s Crypto Mondays. She encouraged me to learn about NFTs. She was right, of course.

My initial thoughts were that this is revolutionary and that to be able to think about it realistically and respond to it effectively, I needed to learn a lot more about it. So, I enrolled in a program at the MIT Media Lab and earned a professional certificate in cryptocurrency. But I waited to begin any drops of my own work for a very long time, despite several offers by different people. Through Victor Acevedo, I met Dina Chang, who was a co-organiser of NFT Tuesdays and who invited me to speak to their group. She further informed me of the potential of this new distribution and authentication process.

To date, I have only released one NFT. I chose to work with Olena Yara, because I trusted her to handle my work, in this case a very old work, with the necessary care and context. But I expect to do many more.

Rodni: Did you see the creation of digital scarcity as inevitable?

I understand why artists rely on scarcity and why, historically, they’ve had no choice. Scarcity has been one of the few mechanisms available for making creative labor economically sustainable. But I find myself wishing we weren’t so dependent on that single economic model. Digital technology, at a fundamental level, does not produce scarcity; it produces mass distribution. It is structurally, even philosophically, the opposite condition.

In that sense, I can accept ultra-rare NFTs as a form of contemporary patronage, a deliberately constructed scarcity that allows collectors to support artists by owning an asset engineered to be unique. That model has its place. What feels underdeveloped, however, are the other possibilities. Why not imagine parallel systems, subscriptions, tiered access, and lower-cost editions that allow far more people to encounter the work while still compensating the artist? Ownership has never been a prerequisite for appreciation. Museums are built on that premise. So is the web. We routinely see images, hear music, and read texts, often without paying directly for each encounter, yet we still recognise that artists deserve to be paid for their labor.

The challenge, then, is not whether artists should be compensated, but how. We need to think more imaginatively about new economic structures that reward contribution without defaulting to artificial rarity as the only viable solution. I believe those models will emerge, not fully formed, but iteratively, through experimentation and necessity. I would love to be part of that discussion.

Recorded music history offers a useful analogy. In the days of music recorded on analog tape, ultimately, a master tape was created. Someone owns the master tape; it is singular, controlled, and scarce. And yet millions of people can listen to the song. That is one of electronic media’s great strengths, its ability to make the rare ubiquitous. The visual art world, by contrast, was built, by technical necessity, on scarcity. A painting was a handmade, one-of-a-kind object; even in a series, each piece remains materially unique. A digital file breaks that logic entirely. It can be shared and distributed instantly, across billions of devices. Technologically speaking, it is the inverse of the handmade painting.

The tension between these two realities, scarcity as economic necessity, abundance as technological fact, is where the next chapter of art’s economy may well be written.

The universe as we currently understand it has virtually limitless abundance. Scarcity is an aberration. My wish is for scarcity to be replaced, rendered obsolete, and that both rightful compensation for someone’s work is paid and creativity is rewarded, while simultaneously allowing free and open access to work. Smarter minds than mine can surely find a way to do that.

Rodni: What are your thoughts on the current digital art landscape? Do you have any predictions on how the digital art market will evolve in the near future?

Today’s digital landscape is so diverse and varies dramatically from region to region. There is no single landscape. I see the developments around the world as being emblematic of the growth and acceptance of digital. Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Latin America and the South Pacific all have had excellent exhibitions, conferences and festivals. This is very good to see. Los Angeles, sadly, so far is still more conservative and needs to awaken to the reality that we are now living in the second quarter of the 21st century. And that digital art is not only here but has been here for a very long time.

But progress continues, and each year it seems to accelerate. Museums have presented major exhibitions of both classical and current digital art and are adding digital works to their collections. In 2024, the Victoria & Albert Museum did a year-long exhibition on the career of Patric Prince, CyberSpace Gallery’s co-founder.

What I expect now is not a single breakthrough, but a number of significant steps. Several things are already happening at once. First, digital art is moving decisively toward the centre of mainstream art discourse. As it should. It is, in a very real sense, the native art form of our time, the one most deeply entwined with the technologies, economies, and modes of perception that shape contemporary life.

There are still obstacles imposed by the traditional art world, but many of the old barriers are finally giving way. The 2025 edition of Art Basel Miami marked an undeniable moment of institutional validation for digital art. It was preceded by a series of important milestones: initiatives like The Digital Mile, the Lumen Prize, and publications such as NFT Magazine and Right Click Save, and so many other emerging voices are all actively constructing the intellectual and market infrastructure the field requires. Every art movement depends on such partners: writers, historians, curators, museologists, collectors, and of course, the general art-loving audience, to form a sustainable ecosystem.

Alongside that shift comes a long-overdue recognition of digital art’s history, with its more than seventy years behind it. As institutional bias against digital media continues to erode, artists who were once overlooked or dismissed will be discovered. Their work will be collected, contextualised, and, inevitably, absorbed into the canon. With that process will come a deeper connoisseurship, one that recognizes the distinct technical “periods” of early digital art and understands how specific tools, platforms, and constraints shaped aesthetic outcomes. Likewise, I believe some collectors, both private as well as museums, will see the importance of preserving the hardware that made these various artistic periods possible. These artifacts will inform future generations about how the work was created.

And of course, we cannot fail to mention the obvious paradigmatic shift that has occurred within the last few years with the rapid widespread adoption and implementation of AI. It seems as if we have quickly jumped into a new state of the human condition. I don’t know how accurate predictions are concerning the inevitability of machine sentience, but it is reasonable to assume that we will be addressing an existential transformation in the near future, where art may not only be interactive, but perhaps even self-aware. I am fascinated by these questions and recently was asked to briefly address an AI conference, consisting of luminaries such as Ray Kurzweil, Natasha Vita-More & Max More, about my thoughts concerning AI and art. Of course, I said that AI in art is here to stay. I also acknowledge and want open and honest conversation concerning the ethical and legal implications. We can both adopt this innovation, while taking care to anticipate the potential risks. But I think we can categorise art, and culture as a whole as “before computers,” and “after computers,” and now also “before AI,” and “after AI.”

Digital art, it should be said, is not a single movement but many unfolding simultaneously. Some will endure; others will fall away. That is the natural course of cultural evolution. What feels different now is the solidity of the ground beneath it all. The conditions are finally in place for the second quarter of the twenty-first century to fully embrace digital art as a major, legitimate, and enduring force. The fact that the UK has only just formally recognised digital art as an official category is less a late arrival than a telling sign and encouraging testament, that institutional acceptance is, at last, catching up with cultural fact.

One thing I’d like to add. Digital art can serve as an exemplar to better understanding the human condition. The digital art landscape has become central to increasing public awareness in the recognition of the increasing understanding of the complexity of human diversity and pluralism. Recently I collaborated with a group of five women; Cally Lindle, Edith Sööt, Nikolina Lawless, Makani Nalu &Alina Kalinouskaya, on a project called “TheAnalog Brain.” It was presented at Lois Lambert Gallery in Bergamot Station Arts Center, as part of the 2024 Getty Museum initiative “PST: Art & Science Collide.” Using low cost digital tools, these five women all explored very difficult themes, including self-harm and questions about the very nature of our reality. Nikolina Lawless, who was as an adult was diagnosed autistic, created several works exploring neurodiversity. One of these pieces was “Eye Contact,” which she performed twice, including once for EZTV’s participation in Frieze LA. This is a logical expansion of EZTV’s decades of commitment to offering production & exhibition opportunities to every variation of this amazing species we call humanity. I feel that digital art and its tools are perfect for creating works that interrogate and investigate all the varieties of what is means to be human.

Rodni: During the tougher times at EZTV, can you tell me what motivated you the most to keep carrying on John’s legacy, and to not hand over the responsibility to someone else?

I must give credit to the great father of the psychedelic era Dr. Timothy Leary. Tim was a patron, a collaborator and a friend. When John Dorr died in 1993, ia Kamandalu and I, working under the name Vertical Blanking were rising in popularity and opportunities. SONY was lending us unique innovative technology, we were being invited to perform, and influential events and things were looking very promising. The logical and economically prudent thing for ia and I to do, would have been to abandon EZTV. But Leary invited us to his home, took out his finest whiskey and as we drank it he predicted exactly what was going to happen. He said “let’s face it Michael, we both know you’re not going to let EZTV die. You are going to stay and save it. So since we’ve fingered that out, now the real question is just how are you going to do that?” 33 years later, I’m still trying to figure that out.

As far as turning it over to someone else, Kate Johnson, had she not passed away at age 50, would have been the person to continue the legacy. She arrived six months after John died, and was transformational in continuing to evolve and continue it. She was beyond brilliant, and I expect that her art will become iconic in digital art history. She deserves it, and I think she would have fit perfectly in today’s world.

Olena: Your practice, and the archives of many EZTV artists, was presented at the Pompidou Centre’s Kandinsky Library. Can you tell me more about your archiving and preservation work of EZTV’s early media works? Can you tell me what EZTV stands for now? And what the future holds for it?

The slow process of “historification,” archiving EZTV’s early work, has been unusually complex, mostly because so many curatorial and production timelines have overlapped. I really began that work back in 1995, when I started digitizing some of EZTV’s earliest projects.

A major milestone came in 2011 with the Getty Museum’s region-wide initiative Pacific Standard Time: Art in LA 1945–80. Thanks to artist/curator Clayton Campbell and independent curator Alex Donis, EZTV (founded in 1979) was officially included through the exhibition COLABORATION LABS at 18th Street Arts Center. That led directly to the USC Libraries’ ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives acquiring a substantial portion of the EZTV archive, videos, photographs, writings, press materials, posters, and artworks, and digitising much of it. For EZTV’s 35th anniversary in 2014, USC expanded this work with a three-month series of exhibitions, screenings, and panels, culminating in large-scale outdoor projections and telepresence art.

In 2019, for EZTV’s 40th anniversary, French scholars Sibylle de Laurens and Pascaline Morincôme, working with the Kandinsky Library at the Centre Pompidou, presented works and archival materials from EZTV in Paris. Their research later became a major website focused on EZTV’s early narrative and digital art, including a long essay they invited me to write about that history.

In 2024, EZTV marked its 45th anniversary, and 40 years of collaboration with LA ACM and SIGGRAPH, by co-creating DNA Festival Santa Monica along with Robert Berman and Jeff Gordon. This year-long survey of digital art included a month-long retrospective of four decades of work, curated with Joan Collins and Victor Acevedo at Santa Monica College. The college is now publishing a catalog documenting both the exhibition and the broader festival.

More recently, through the efforts of UCLA digital archivist Jackie Forsythe and T.A.P.E., additional EZTV works are being preserved and digitised.

Today, EZTV continues to collaborate across many media. A dedicated physical space is no longer essential, artists have easier access to tools, and online distribution makes international visibility routine. Looking ahead, we’re focused on what’s next: working with scientists and technologists as much as with other artists, building global collaborations, and participating in festivals, fairs, conferences, and exhibitions. We want to show new work, and also revisit the past, not just for context, but because the work still holds up.

Rodni: So many incredible people made EZTV what it was. Can you tell me more about what bonded and motivated you and Kate Johnson, Zina Bethune, Mark Gash and all the others who made EZTV truly special?

In each of the cases you mention, the answer is deceptively simple, EZTV was the only place where the work they created could exist at all. It is striking that the three artists you cite have all since passed away. Each was a titan in their own right and saying a few words about each helps clarify not only their importance, but why a space like EZTV matters.

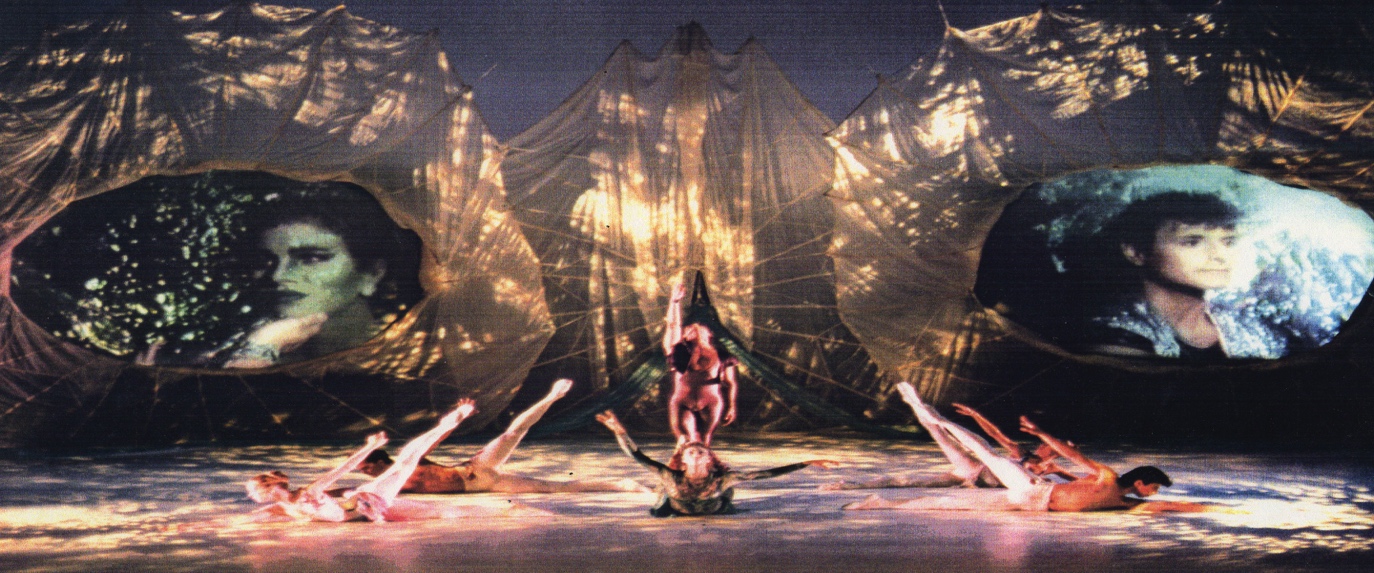

I’ll begin with Zina, the eldest of the three. Even now, I struggle to understand how her life is still not widely recognized. Her life prior to arriving at EZTV reads like fiction, it’s so extraordinary that it genuinely deserves a film of its own. At six years old, she was simultaneously a dance prodigy under George Balanchine and a working child performer on stage and screen, appearing in projects connected to figures like Tennessee Williams. By sixteen, she was a national television star. At 22 she starred in Martin Scorsese’s first feature film. Then came a devastating turn, multiple genetic conditions led doctors to tell her she would never walk again, let alone dance. She proved them wrong. She went to Denmark and volunteered for new experimental surgeries. Not only did she return to dance, but she also performed on Broadway as well as the White House, Kennedy Center and in 1988 in China. She went on to teach thousands of disabled children how to dance, each in ways adapted to their own bodies and abilities. When we met in 1987, we began collaborating on some of the earliest multimedia projections ever paired with live dance in Los Angeles. We then advanced to using robotic sets and moving projection screens, using night-vison cameras in live performance, projected onto smoke and rain, and experimented with ways to blur the lines between the live stage and the projection screen. What she created at EZTV could not have happened anywhere else.

Kate was unstoppable, an artist of extraordinary range and momentum. Her father, a corporate executive, insisted she earn a business degree, hoping she would follow a conventional path. She did earn it, but alongside her studies she performed with modern dance companies and experimental theatre groups, worked as a photographer, and taught herself computer coding and video production. She became one of the earliest figures to teach digital production at the American Film Institute, then spent two decades teaching digital media at Otis College of Art and Design. She was beloved by her students, some who went on to intern and even work at EZTV. Her multimedia performance works were both formally rigorous and emotionally arresting, and she produced some of the largest and most ambitious projection-mapped works seen in Southern California. Iconic buildings such as LA’s City Hall, and the Getty Museum became her projection surfaces. Remarkably, her first attempt at producing a documentary for PBS (America’s public television) won an Emmy. Before it ever aired, it premiered at Lincoln Center in New York. A straight cisgender woman, she was largely responsible for the preservation of the early EZTV archives, including a seminal collection of Queer-centric media work. She saved EZTV and the City of Santa Monica had named an annual media arts fellowship in her honour. And that is only a fraction of her output.

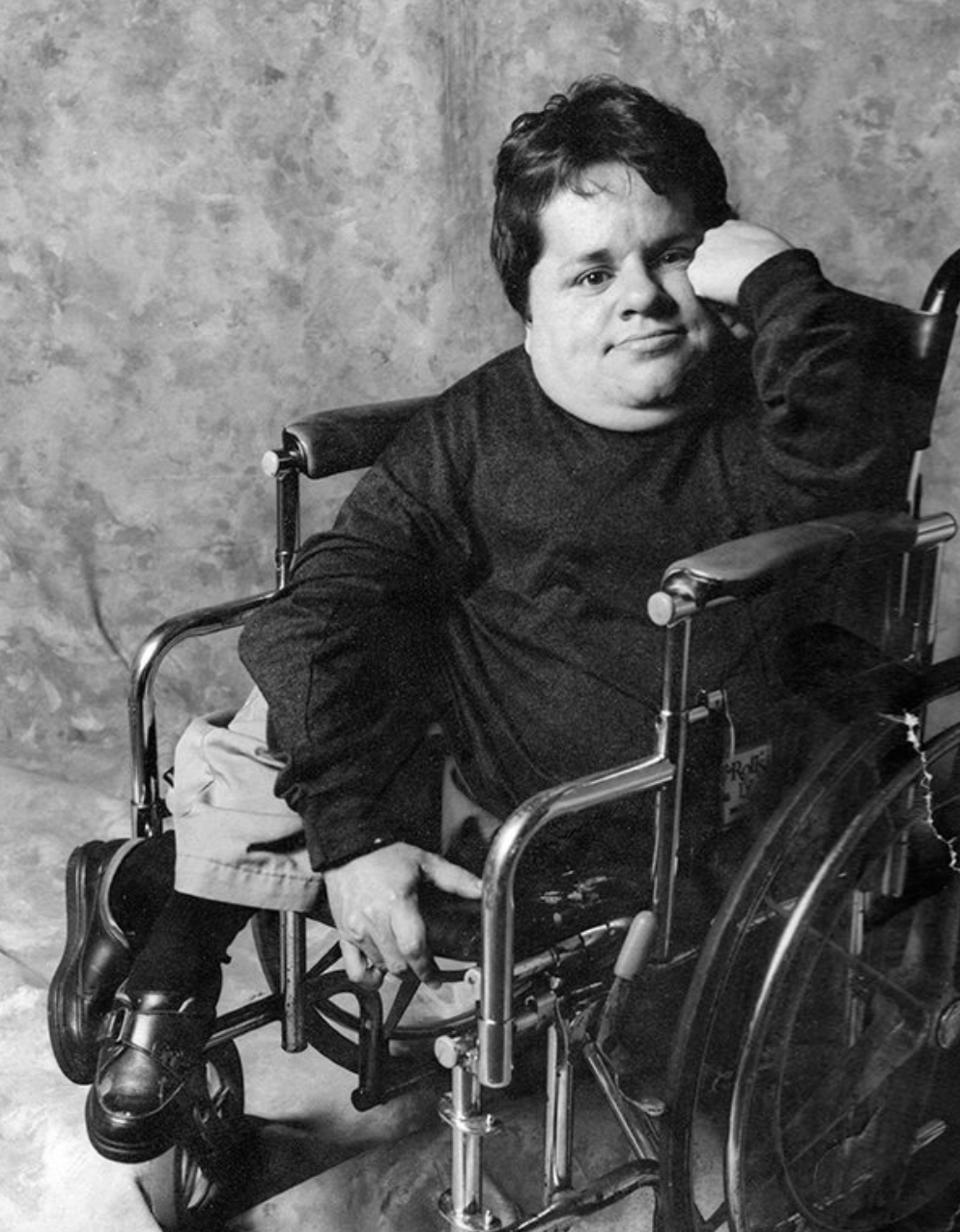

Mark was equally singular. Born with the most severe form of osteogenesis imperfecta (brittle bone disease), he entered the world with more than a dozen broken

bones and endured countless additional broken bones and fractures over the course of his forty years. He nonetheless became the first person with his condition to graduate from college, then exceeded even that milestone by earning a graduate degree. He studied painting at the California Institute of the Arts under John Baldessari and went on to produce more than two hundred paintings, many of them large-scale. He drew cartoons for LA Weekly, created performance art, wrote plays, curated wall exhibitions for EZTV, and taught art within the Los Angeles prison system. He even appeared, playing himself, in a cameo role in William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. Late in his life, he taught himself digital production, built EZTV’s first website, and began developing interactive artworks—work that was only just beginning to unfold when he died. He could have easily used his condition as an excuse for not doing anything with his life, and to simply feel sorry for himself. Instead, he used his situation as an mandate to achieve, to prove that persons with his condition can live full, creative, productive and influential lives. And he certainly proved that was the case.

EZTV is, at its core, the story of people who came together to build an alternative to what already existed, because what existed had no room for them. Zina, Kate, and Mark are three among many who make EZTV’s forty-seven-year history singular. Their lives, their work, and their contributions deserve to be remembered, seen, and understood. Part of my mission now is to help ensure that they are.

To me, the most interesting art is tied to a narrative, an artistic movement, a socio-political struggle, a quest for new ways to express, both through innovations in concept as well as the tools utilised. To someone interested in how art can incubate, proliferate, distribute and perhaps someday even be historicised, EZTV is a story worth exploring. And these three artists you mentioned are very clear examples.

Rodni: Looking back on all your EZTV years so far, is there one particular moment or milestone that stands out to you as the proudest? Something that still brings a real sense of accomplishment or joy when you think about it?

I think that maybe something that was initially intended to be a joke but took on a life of its own and grew much larger than me or EZTV. The West Hollywood Sign taught me in no uncertain terms, the power and meaning of art and how art can have value beyond merely economic value. Now the West Hollywood Sign was a decidedly analog artwork. It was made of plywood. I was born in the South Bronx. Birthplace of Hip Hop and a central location for the modern graffiti movement. So, as a joke, and without permission from the landlord, we installed a 40 ft. sign saying “West Hollywood” on a hill overlooking the parking lot of EZTV. And on the 30th anniversary of the invention of videotape, we held a press conference and declared West Hollywood ‘the video capital of the world.’ It was part sculptural graffiti, part performance art, and part spoof of the still un-respected role that video played in the entertainment industry.

We expected the police to arrive, fine us, give us citations, and tell us to take down the sign., Instead, the press came and loved it. Soon, the mayor and other politicians came and posed in front of it. The owner of the land never said a word. People would begin stealing letters, and for a while, I’d make replacement letters. That lasted for about five years until I got tired of making new letters. Ultimately, every letter was stolen, and the sign disappeared. I regret never having kept one of the letters for myself.

My life went on, and I stopped thinking of the sign, although people would occasionally ask about it and tell me how much they loved it.

Decades later, a young Queer journalist published a blog post asking if anyone remembered it. And then it was both heartbreaking as well as most gratifying to me as an artist, he said, “when I was a teenager, and my mom would try to beat the gay out of me, I would think of the West Hollywood Sign.” I cried when I first read that.

What began as a joke became a symbol of pride for a community and a city. And taught us how art can impact the lives of people the artist may never meet. And that is the power of art, and something for which I am very proud to have created.

Olena: We’re both currently working on Pavuk Live with Alina Kalinouskaya, with the aim of raising funds for Ukraine. Why did this theme feel relevant for you to engage with at this moment?

I have always believed that art is a catalyst for positive change. And have always tried to do my part to help make things better. I began as a Rock ‘n’ Roller’ playing my electric guitars so loud that I’m deaf in one ear. But rock music and many forms of popular music inspired people to change. All art can do that. EZTV has always wanted to help.

Alina Kalinouskaya is a performance artist here in Los Angeles. She has been associated with EZTV since 2018. But she was born in Belarus, and her mother was born in Ukraine. During the Christmas holidays in 2025, Alina was upset about the destruction of critical electrical systems in Ukraine, resulting in the people facing extreme cold and darkness. She wanted to do something about that and asked for my assistance. She came up with the brilliant idea of collectively creating a Pavuk, a traditional Ukrainian symbol of university unity and peace.

I suggested she contact you as well. Through your efforts, Alina has now met several artists working in Ukraine who will collaborate with her, along with other international and local artists. Together they will create an art installation, finished by the legendary performance art group LA MUDPEOPLE. Alina will do a durational performance work, bound motionless by red ropes, to remind us that the situation in Ukraine has not changed and to remind us, especially in the U.S., where the chaos of all the noise within the local news has unfortunately taken a focus away from Ukraine, that we must remember and support or brother & sisters there. Alina asked me, along with long-standing EZTV artist Cally Lindle, to co-host the event, which will be live streamed.

The role that art plays in social and political movements has been at the heart of EZTV since its earliest days. The tools and skills of an artist communicate on so many levels. It is visceral and works in ways that pure intellectual discourse sometimes cannot.

This will actually be EZTV’s final event at 18th Street Arts Center, which has been our home for the last 26 years. We will be focusing on our online museum and then setting up a new space soon. We are proud of all the time we spent at 18th St.

Rodni: What else are you working on right now that you would like our readers to pay attention to?

As always, I’m heading in several directions simultaneously. Some leading edge technically, others using the same tools I’ve used for decades.

But my most tech-driven projects involve developing work in what I see as a major upcoming movement within digital art, volumetric imaging. What most people would call full motion, full color large scale holograms. I’m working with Olena Yara, Alina Kalinouskaya and an amazing group of scientists led by Michael Hollins at the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s iEXCEL holographic theatre, in full collaboration with independent scientist Dr. Gregory Captenter, choreographer Donna Sternberg, and producer Rafi Ruthchild. We are currently calling this collaborative initiative holoSTAGE.

iEXCEL is the first holographic theatre in academia. Together we are imagining a series of projects that will be potentially transformative for both digital as well as live performing arts. Life-sized holographic projections interacting with live dancers & performers. The holograms are interactive and AI enhanced. Together we have imagined what I believe are some very compelling art/science projects. I think that projects such as these will exemplify where art if going in the next decade. Of course, funding such projects is difficult but with the incredible team we’ve assembled I believe we will find suitable patrons, supporters and investors. Among the many ways to commoditise these projects will certainly be NFTs, as well as phygital works, plus ticket sales for IRL experiences, and limited-edition fine art installations.

At its core, holoSTAGE is not only concerned with innovative ways for art and science to literally dance together but is keenly aware of the ethical concerns involving privacy, data mining, copyright infringement, and other legal and moral concerns involving the integration of AI and online databases into creative work. Each project will in its own way, address these issues and perhaps develop protocols to mitigate these concerns.

In a completely different direction, I’m working with Performance Artist the Dark Bob (of the legendary 1970s-80s performance art duo Bob & Bob) on a feature-length documentary on some of LA’s most influential performance artists, critics, and curators.

And about to go into print is a catalog/book that focuses on our 2024 year-long initiative DNA Festival Santa Monica. Originally intended to be just an exhibition honoring EZTV’s 45th anniversary and its 40 years of collaborating with LA ACM SIGGRAPH, it expanded into a 26-event, 9 venue survey of digital art, both contemporary as well as classic. We are hoping to do another DNA Festival in the near future.

And for much of the last 15 years, I have been simultaneously building towards the future, while preserving the past. Our EZTV Online Museum will soon undergo a long-overdue and much-needed update. There is so much that has happened that is still not online. I need to fix that.

And of course, I would like to do more NFT drops. I would mint both old work and current work. In so many ways that will be how we, as digital artists, truly differentiate ourselves from older, more traditional media. We need both the old and the new, the physical and the digital, the present and the telepresent, the IRL and the online, all creating and experiencing together. And I see exciting times ahead.