Gazelli Art House presented the first solo booth dedicated to generative art at Frieze Masters with momentous drawings and paintings by Harold Cohen – one of the first artists to explore artificial intelligence as a tool for creating art, through his pioneering programme named AARON.

Cohen was regarded as one of Britain’s foremost painters, with solo shows at the Whitechapel Gallery and representing Great Britain at the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966 before he was first introduced to computing. The works on display at Frieze Masters emphasised continuity across Cohen’s practice – from his early abstract canvases of the 1960s, to his 1990s works such as the Painting Machine series, revealing a lifelong exploration of rules, systems, and perception in the creative process. This trajectory underscores Cohen’s dual legacy as both a painter and a pioneer of computer art, situating his practice within the history of post-war British painting while tracing its role in the emergence of generative art.

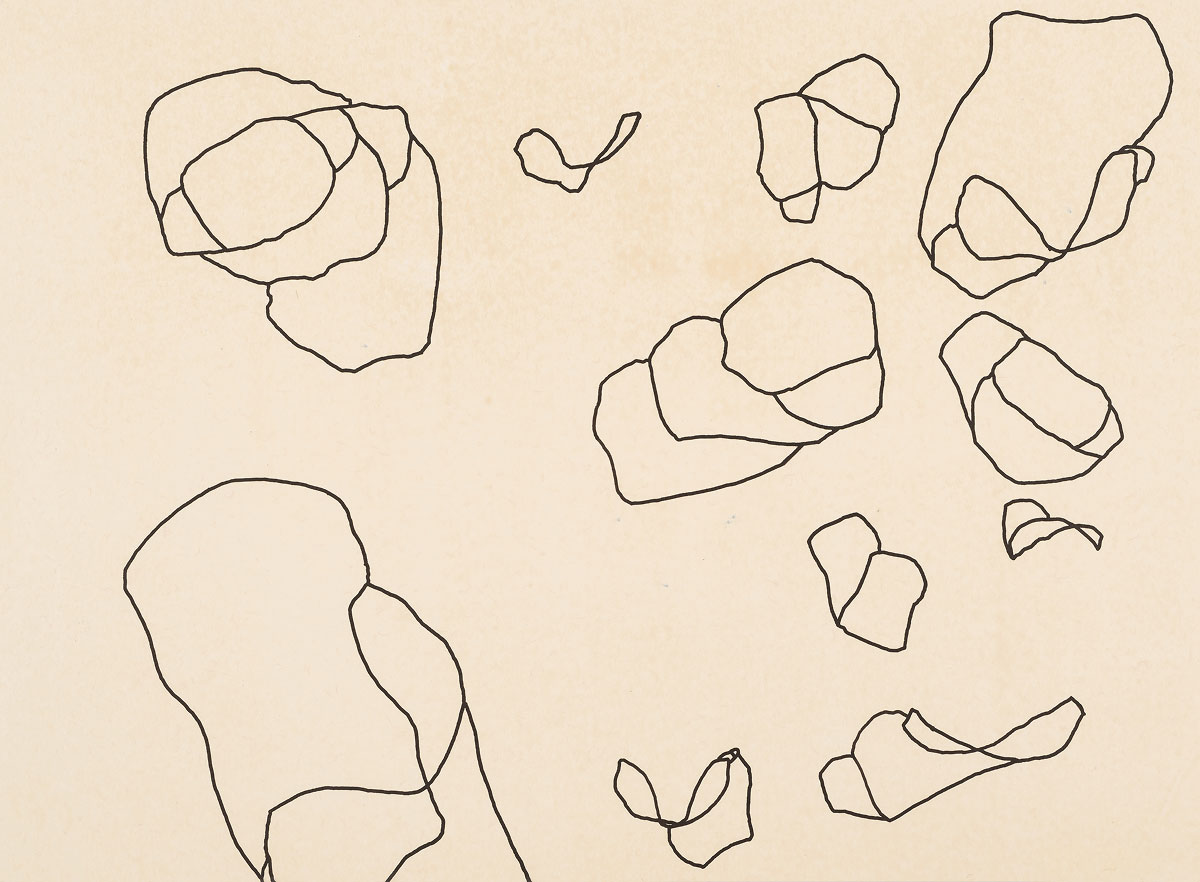

Highlights of the booth include works from Cohen’s pre-AARON period alongside examples generated with AARON, charting his shift from canvas to code. Among them is a 1983 drawing produced live by AARON during Cohen’s exhibition at the Tate in London.

Unlike today’s AI creation tools that pull from huge data sets of online images and use complex systems to match a users’ prompts to those images – Cohen wrote his programme to autonomously create art by following rules that mimicked how an artist thinks. AARON works like a robotic artist following a guidebook Cohen wrote in code (using languages like C and later Lisp). This guidebook contains instructions, or “rules,” about how to combine simple shapes (called “primitives,” such as lines and curves) into recognizable objects, like a person or a plant.

When Cohen first created AARON in the late 1960s, it could only draw abstract lines and shapes because those were the only rules it had. By the early 1980s, Cohen added new rules to teach AARON how to draw people. For example, he programmed it with instructions like “a person has a head, two arms, and legs” and “arms bend at the elbow.” Using these, AARON could build a human figure by connecting lines for limbs, adding a head, and placing it realistically in a scene.

Around 1983-1984, Cohen expanded AARON’s guidebook by programming rules for drawing rocks, part of what he called the “rock-art paradigm.” These rules told AARON how to create rock-like shapes and how to place them in a landscape, like at the bottom of a scene to suggest ground. Once these rules were added, AARON could choose to include rocks in its images, just as it could choose people, because its “vocabulary” of possible objects now included both.

Over time, Cohen kept adding more rules, teaching AARON to draw plants, trees, and even indoor scenes with furniture by the 1990s. Each new set of rules was like giving AARON a new art lesson, expanding what it could draw.

When deciding how to compose a piece, AARON follows a process where the number of elements is determined by Cohen’s rules for balance and composition, with some randomness to keep things varied.

AARON starts by dividing the canvas into sections, like the foreground, middleground, and background. Cohen’s rules then guide it to make the scene look balanced – not too crowded or too empty. For example, it might decide the center needs a main object (like a person) and the edges need smaller ones (like rocks or plants).

Once the layout is set, AARON picks what to draw from its “menu” of objects (e.g. people, rocks, plants) based on the rules Cohen gave it. It doesn’t need the artist to prompt it by saying, “Put two people here.” Instead, the rules include ideas about how many objects make sense for the scene’s size and balance. For instance, a rule might say, “If the canvas is large, include 1-3 main objects (like people) and 2-5 smaller ones (like rocks).”

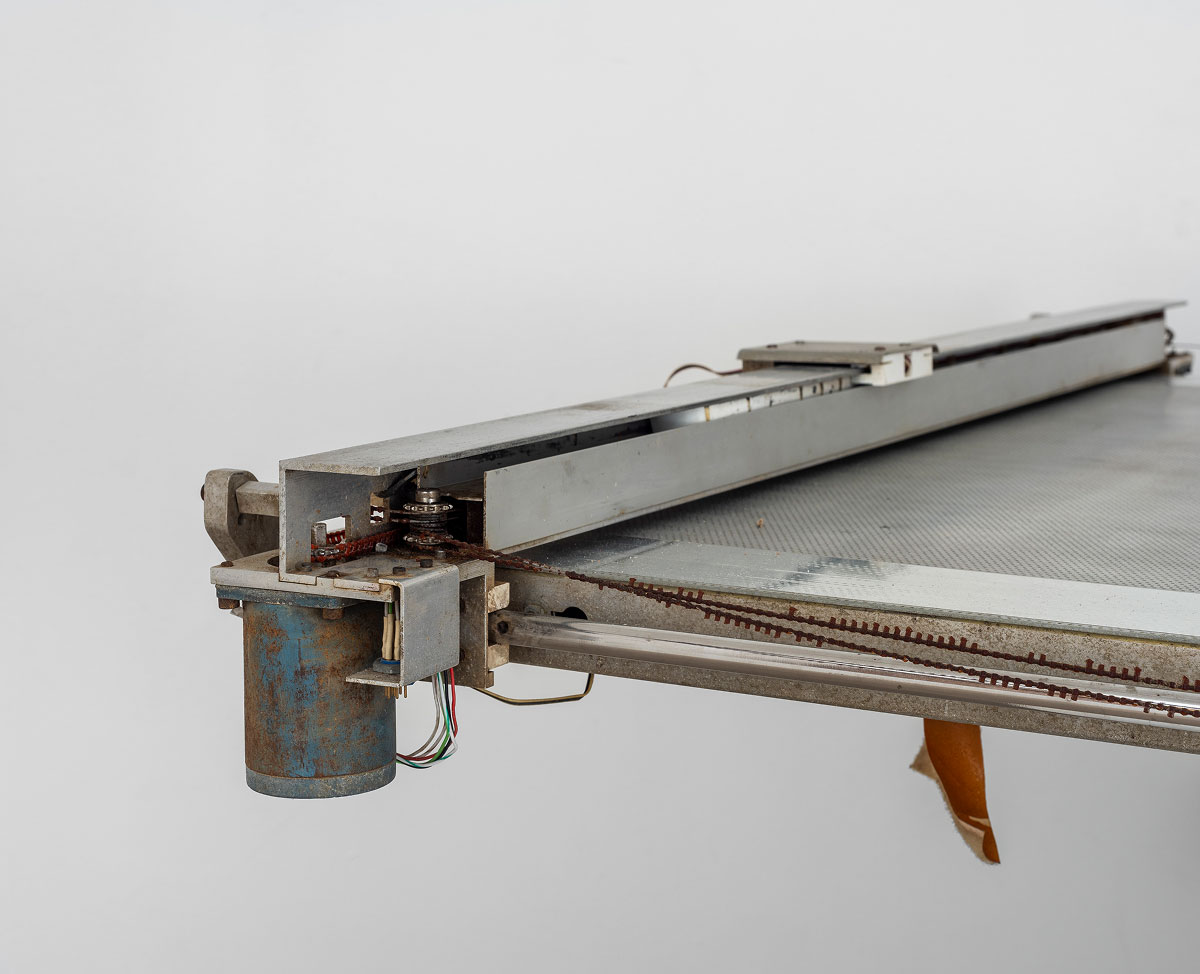

After deciding what and how many objects to include, AARON builds them using its primitives (lines, curves) and draws them with a plotter (a pen-moving machine). By the 1990s, it could add colours like green for plants or skin tones for people, following rules for what looks natural. The final image, like those shown at Frieze Masters 2025, is a complete artwork that looks planned, not random, even though AARON made the choices.

Gazelli Art House’s impressive presentation displayed Cohen’s original Drawing Machine alongside a screen-based display of the revived code, extending his legacy into the present. Echoing the Whitney Museum’s landmark exhibition Harold Cohen: AARON (2024), which reintroduced live plotting to museum audiences for the first time since the 1990s, the installation underscored both the historical importance and contemporary resonance of Cohen’s pioneering programme.